|

Seeing, but Not Looking...

Seeing, but not looking; hearing, but not listening; touching, but not feeling…are the harbingers of mistakes in the landscape at the hands of human beings. When cognitive and sentient attributes are ignored, humans diminish their innate gifts. Lost as well are the inherent gifts present in the landscape. By merely occupying the landscape some humans advance design decisions which creates separation from natural form and function. Managing resistance becomes the modus operandi. What ensue are landscapes that are visually artificial, contrived and staged with little to no connection to place. Purpose and use are imposed; rather than cultivated. Consequently, these landscapes are costly and more importantly, they are not healthy and vigorous.

Any effort to reduce or eliminate common and not so common mistakes begins with a change in attitudes and values. Willful and ego driven decisions are supplanted by thoughtful, careful observations, among other things. Curiosity and wonder dominates in advance of any judgment and action. Acceptance of our natural heritage is an important perspective, serving this visual guide. We live in a temperate region: temperatures fluctuate dramatically as a function of season. Historically, the landscapes, in question, were part of a larger transitional zone from a mixed deciduous hardwood forest to a tall grass prairie, interspersed with open savannahs – east to west. These characterizations, in part, are the DNA of this visual guide.

The proceeding brings into focus the assertion that visual mistakes are mutable and amiable to correction. Healthy and vigorous landscapes based upon cogent and creative adaption are: financially prudent and visually attractive. Specifically what follows is a cycle presenting: descriptions of mistakes; rationale or reasons why mistakes are problematic; and remedies or corrective actions.

|

|

Dead or Alive

Description: River gravel and a disassembled artificial Christmas tree are presented as a foundation planting bed.

Problem: This presents a mistake on two accounts: management and aesthetic. River gravel stores and transfers heat in a manner that exacerbates any effort to cool this office in the summer time. Aesthetically, an inorganic presentation bed, gravel and a bottle-brush artificial Christmas tree, falls far short of the possibilities for a suitable, attractive planting bed.

Solution: Remove the existing features, test the soil, amend as needed and cultivate the soil. Given the configuration and surface area, the planting bed would only support a groundcover and shrub layer. The Garden’s Plant Finder would be a great source for identifying suitable plants for full sun and dry soils.

ProblemSolver Plants for Shallow, Rocky Soil

|

|

Help or Harm

Description: Subsurface irrigation system placed in the soil.

Problem: Far too often, even with timers and monitoring systems, irrigation poses a host of problems. System failures, both hydrologic and electrical, can be marginal to catastrophic in scope. Even when irrigation is operating “properly,” plants often get watered too much leading to shallow rooted plants. Plants placed in intensive care become susceptible to uncharacteristic animal browse as well as disease and insect vectors. In the absence of a system relying on grey water, the use of expensive, precious municipal water is indefensible.

Solution: The best irrigation system is a well-managed soil. The proper balance and proportion of air, mineral and organic components make for the best irrigation system. The presence of micro-biological activity needs to be acknowledged as well. Choosing the “right plant for the right place” is paramount for any success to have a chance.

|

|

Easy But Not Appropriate

Description: Subsurface plastic drain pipe aligned on the surface and in the turf.

Problem: This is at best a misapplication of materials. Maintenance wise who wants to cut grass around this barrier. Using a line-weed trimmer over time chews-up the pipe only to leave pieces in the turf as waste material. The plastic obstruction is a safety hazard which poses a risk to children and adults alike. Aesthetically, a drain pipe in the turf is plain ugly to the discerning eye.

Solution: Use the material and fasteners as designed and manufactured. Place the subsurface drain underground. Any final alignment should include good positive drainage from the downspout to an outfall pipe or pop-up emitter.

|

|

Garden Gold at the Curb

Description: Neatly placed bags of fall leaves at the curb are to be picked up by a municipal waste service.

Problem: Fall leaves are not waste. An expense is met in the fall to remove the leaves. And in the spring an expense is met in purchasing mulch. This is clearly not the most prudent allocation of dollars and cents.

Solution: Composting leaves on site has two benefits. First, the leaves with a proper mix of grass cuttings will decompose to “Garden Gold.” Second, you will save on a gym membership by getting great exercise out in the open air. The best practices for creating and maintaining a compost bin(s) can be found in the following factsheet:

Composting Yard Waste

|

|

Irreconcilable Differences

Description: A line of trees and power lines are assuming the same air space.

Problem: Power lines and trees are not compatible. Each is denied their full performance potential. When performance potential is in jeopardy, the power lines always win. Hands down.

Solution: It is essential that the selection of larger shrubs, understory and canopy trees is done so with great care. The finished spread and height of any given plant must be part of the calculation in siting a plant.

|

|

High Demand and Needy

Description: A front yard is presented with a monoculture of turf.

Problem: Plant communities, simple or complex, evolve over time from a monoculture to a diverse culture. Plant succession will have its way in the absence of major, costly interventions. Turf as a default feature in any landscape is really a “fool’s errand.” A monoculture of turf is under constant siege from wind and animal dispersal of seeds and nuts.

Solution: Work with the ebb and flow of nature and site. Reduce turf to serve essentially three purposes: 1) service access, 2) active recreation and 3) an aesthetic focal point.

|

|

Beware: Wet Zone

Description: A grass swale has been provided to manage both sheet drainage as well as drainage across a flow line that runs from a high point to the open catch basin. Storm water originating on-site and off-site is accounted for.

Problem: Far too often grass swales devolve into an urban or suburban bog condition. Saturated soils are difficult to manage, plus they pose a safety hazard. We would never introduce turf where heavy vehicular circulation is going to occur. Why do we persist in introducing grass to manage for the engineered circulation of storm water?

Solution: There are three remedies with commensurate levels of performance.

First, remove the turf, don’t amend the soil to increase porosity but introduce deep rooted plants at the groundcover and shrub layer. The expense is low and the performance is low as well.

Second, remove the grass, amend the soil to increase porosity and introduce the appropriate plants. This remedy known as a rain garden holds a middle position on the gradient of expense and performance.

Third, remove the turf and soil; introduce river gravel or river jacks along the flow line from a high point to the open catch basin. A dry creek comprised of a site-specific alignment with the proper subsurface contours and finished edges will function as, or mimic, an ephemeral stream, which can be found in nature. This remedy holds the highest position on the gradient of expense and performance. When planting beds are included thoughtfully what is a site constraint becomes an aesthetically pleasing landscape feature. This last remedy presents the most attractive views from both the house and garden.

|

|

When Soil Creeps

Description: The soil on this steep slope is in a state of failure.

Problem: This soil has been finished graded to a degree of slope it cannot support. The angle of the slope is such that when the soil becomes saturated due to a rain event, it loses it structural integrity. The soil creeps down the slope. The grass cover is no help in mitigating this condition.

Solution: Slopes can be thought of as slight, moderate and steep. Each has its own limitations and benefits. However, in the main it is best to avoid steep slopes whenever possible. In this case, because turf has shallow roots, the grass does not have the physical or mechanical means to support this grade. Further the roots of turf are providing limited coverage because they are constantly undergoing a cycle of dying and being replaced with new growth. In the alternative, the grass needs to be removed and replaced with native grasses, flowers, shrubs and understory trees. These plants by type have roots that possess the physical and mechanical strength to mitigate this grade.

Plants for Erosion Control: Grasses

Plants for Erosion Control: Herbaceous Plants

Plants for Erosion Control: Trees and Shrubs

|

|

Too Much, Way too Much

Description: This Bradford Pear is buried in mulch.

Problem: Too much mulch around the base of a tree is problematic for a host of reasons. They include, but are not limited to, the following considerations. An excessive amount of mulch at the root crown inhibits the exchange of gases and nutrients which supports the tree. The mulch necessarily settles and becomes compacted. Instead of infiltrating rain water it sheds it. Too much mulch provides cover and shelter for small mammals. Timing is an issue as well. During the winter months, mice and voles can hide out in the mulch taking refuge from the cold. They chew on the bark of the tree, exposing the cambium. This in turn later compromises the translocation of both water and nutrients. These small mammals hidden from view avoid predation. Insects, as well, overwinter in this thick layer of mulch. Consequently, the prospects of insect and disease vectors are increased.

Solution: The root crown of a tree should be free of mulch by several inched in its circumference. Three to four inches of mulch should be introduced beyond this first circumference to a much larger one. The surface area of the mulch is determined by the size of the tree as well as the availability of space. The benefits of a properly mulched tree is twofold. First, it provides physically a setback which minimizes the prospects for tree trunk damage due to lawn mower use. Second, this area provides an opportunity for the introduction of plants at the groundcover and shrub layer. A remedy of this type makes for a more appealing transition from turf to specimen tree.

Woodland and Shade Gardens - Herbaceous Plants

Woodland and Shade Gardens - Woody Plants

ProblemSolver Plants for Dry Shade

|

|

Too Little, Way Too Little

Description: A precast concrete block retaining wall is used to confine a mature tree.

Problem: The finished circumference and height of this retaining wall is inadequate. The retaining wall in question is operating like a choke collar. It’s a variation of the problems inherent in introducing too much mulch around a tree. Furthermore, this retaining wall is in failure because it does not have a proper setting bed for drainage. Any retaining wall constructed over soil alone is subject to freeze and thaw impacts.

Solutions: First, layout the configuration and surface area of the wall in a manner that acknowledges the needs of the tree. Second, trench with care. Third, backfill with crushed limestone as a setting bed. Fourth, a minimum of one course of stone or precast concrete block needs to be set-up level below grade.

|

|

Ouch! My Feet are on Fire

Description: A screen of Eastern white pines has been planted on a ridgeline of an earthen berm.

Problem: A combination of berm and evergreen is not always the best solution for screening. The performance is often mixed. The rationale in building and planting on a berm is to improve the soil to plant in and accelerate the benefits of screening; in this case the vehicular traffic. A berm can cause two problems. One, it promotes runoff and discourages infiltration of precipitation. Two, a berm as a convex landform stores and radiates heat above the surrounding ground. Consequently, there are times when the plants are getting inadequate amount of water. Other times, in the summer the berm is excessively hot and is drying out and burning up the roots of the plants.

Solution: Exercise patience. Plant a vegetative screen in an improved soil at existing grade. Admittedly, in these circumstances the soil is a disturbed urban or suburban soil. Hence, a soil test, adding amendments and cultivation of the parent soil may be required prior to planting. These efforts will be well rewarded.

|

|

And the Winner is...

Description: A hedgerow of Eastern white pines has been planted in a colony of cool season grasses.

Problem: The pines and grasses are in competition over time. Shade, dryness and a build-up of pine needles has killed the grass underneath the trees. Consequently, these limbed up pines have created an unsightly patch of bare soil in the lawn.

Solution: First and foremost, respect the natural form of the pines. While too late in this case, do not limb up pines, junipers, arborvitaes, and hollies, among others. Provide for a visual transition between turf and the evergreens. Create an adequate setback as a larger planting bed. A couple of fixes are quite straightforward. One way is with a spaded informal edge. Another way is with stone, brick or metal edging. Either way, if additional plants are desired at the groundcover layer, it is imperative that the surface area and configuration of the bed be well beyond the lower branches of the evergreens.

|

|

Charged But Found Not Guilty

Description: One silver maple has been planted over a lateral sewer pipe in the front yard.

Problem: Plant roots and lateral sewer lines often assume the same proximate soil space. Plants are not the first cause for lateral sewer failure. Yes, often lateral sewers are clogged with roots. But plant roots do not have the mechanical and physical capacity to break-up sewer pipes. What happens is the pipes are subject to soil subsistence which causes open voids under the pipes. This in turn precipitates a differential load across the alignment of the pipe in the soil. A break in the pipe occurs as a result. Another proximate cause is age and weathering of the pipe material. Plants exploit these failures as water and nutrients leach into the soil. The roots are opportunistic actors. They are charged because their root prints are present on the scene. Hence, the pipe itself is the first order cause of failure. The tree is a second order cause of failure.

Solution: Do not fix blame; fix the problem fairly and accurately. Manage for soil conditions and material pipe failure. These are the dynamics. Things wear out.

|

|

It's OK, It's OK

Description: Boston ivy serves as an inviting vegetative brow over the entrance of a brick home.

Problem: Ivy and vines, in general, do not present the problem for the deterioration of brick. Structural brick in mortar fails for a number of reasons: imperfections in the manufacturing of the brick; the laying up of the brick; changing mechanical loads, tension and compression, among others; and, weathering over time. All of these problems exclusively or in combination account for first order failure. The tendrils of ivy do not have the mechanical or physical strength to crack and break brick or mortar. Any contribution by the ivy to failure would only be due to pre-existing conditions. Ivy and vines are supporting actors only in second order failures.

Solution: Do not fix blame; fix the problem fairly and accurately. Remove periodically, ivy and vines in selected areas for visual assessment of the brick and mortar. Proceed with or without a tuck-pointing event based upon assessment. Note, strategically placed ivy and vines actually can have some positive impacts: creating a micro-climate which minimizes the differential heating on the brick face as well as minimizing the cycle of wet and dry brick and mortar.

|

|

It's Not OK, It's Not OK

Description: Trees are damaged as part of a new construction event.

Problem: The bark has been stripped due to heavy construction equipment running about the open, bare site. The cambium is exposed. Consequently, the long term health and vigor of these trees are in jeopardy. The translocation of water and nutrients from the roots to the canopy and food from the leaves to the roots has been compromised. Furthermore, the trees have become more susceptible to disease and insect injury. Even small mammals and birds will exploit trees in decline.

Solution: Little can be done for these trees except monitoring their health and vigor. Tarring over the exposed area is not recommended. This remedy has not been found to have any redeeming benefits. Consequently, today you rarely see blackened areas on trees. This, however, is a case where an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure. Given a new construction event, clear, visible and physical lines of disturbance need to be established as part of site preparation. Generally, flourescent orange snow fencing is placed around plants to be retained and protected. This due diligence is amply rewarded with the new construction nestled in the existing landscape.

|

|

Habit Trumps Judgment

Description: A bright green turf strip delineates and establishes a bold visual property line in the foreground. An open woodland is being re-established in the middle ground. An existing woodland is in the background.

Problem: Design context should not be summarily dismissed. This woodland was cleared initially at its edges for an informal, natural development. Force of habit often is blind to a sense of place. The grass strip in the foreground is only a detail to a property dominated by a monoculture of turf. This landscape not only is aesthetically jarring, it points to a property subject to high maintenance cost. The landscape in the middle ground is a credible attempt to heal the landscape from what was an overzealous clearing of a woodland plant community.

Solution: Acknowledge and respond to the “Genus of Place.” Whenever possible select for low maintenance cost while selecting against high maintenance cost. Less is more. Fertile soils; surface and subsurface water; and clean air are positively protected and improved as first order principles. We all are beneficiaries directly and indirectly.

|

|

Out of Sight; Out of Mind

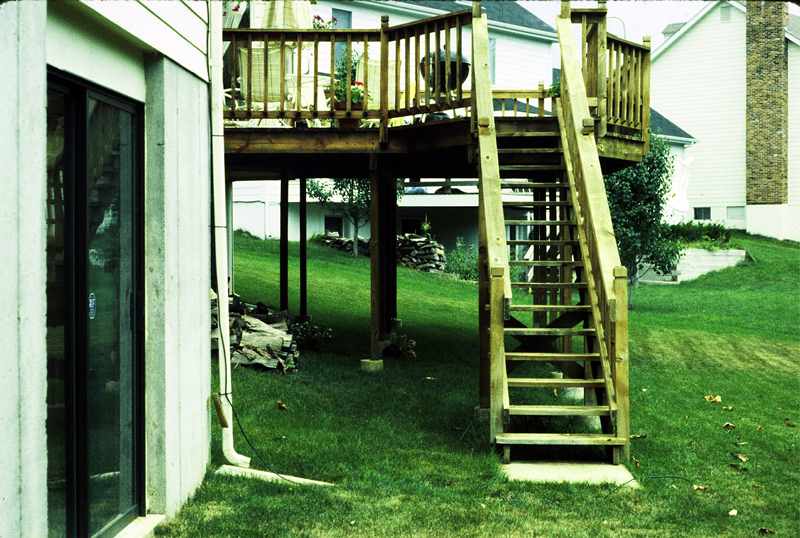

Description: This outdoor deck, cantilevered and post supported, serves a number of purposes. One is for a bird’s-eye view of the garden. Another is for access to and from the house and garden.

Problem: Far too often, the available space below a deck is ignored.

Solution: What is described frequently as “dead space” is anything but. The deck in combination with the space is ripe with aesthetic and practical potential. Architecturally, the deck can be enhanced in a number of ways. A hanging curtain attached to the perimeter of the deck. A wooden curtain, configured as lattice and edged in scallops, draws the eye up and away from the dark space. The posts can be strengthened literally and visually with an attractive large wooden or stone base. The large visual impact of the deck surface in profile is reduced with either enhancement. Another design strategy would be to leave the deck untouched.

Instead, the landscape could be the area of focus. Actually, this is what occurred here. A narrow recharge trench filled with gravel and lined with granite cobbles establishes the outside boundaries of an all-encompassing plant bed. This trench provides subsurface drainage originating at two downspouts. This managed storm water discharges from an outfall pipe into a converted grass swale into a dry creek. The configuration and surface area of the bed are larger and beyond the drip-line of the deck. The space is bisected with pavers to provide a journey of passage and pause below the deck and parallel to the foundation of the house. Several discrete plant communities are established. Each acknowledges the gradient in available water and sunlight.

|

|

Yes and No

Description: Large scale field boulders comprise a handsome retaining wall. Purple winter creeper fills the open voids in the wall.

Problem: The use of on-site boulders to retain a turf terrace in advance of making a vertical change to the grass strip, public sidewalk and street is an unqualified positive…Yes!…The use of purple winter creeper to fill the voids is an unqualified negative…No!...This groundcover is invasive.

Solution: A number of appropriate plants could serve as suitable substitutes. Check it out with a search in the MBG Plant Finder. Consider plants that thrive in a rock garden situation.

|

|

Hey, You're Not Done

Description: Cut stone is used to construct a retaining wall for a tree at a concrete sidewalk.

Problem: The wall is incomplete. The execution of the work is problematic for a number of reasons. While the mix of stones by size and weight is appropriate, the manner in which they were used is not. Having the top course relying on larger and heavier stone could lead to a structural failure. Consider that a retaining wall is subject to three forces: crushing, tipping and rotating across its length and height.

Crushing implies a vertical force that radiates from the top of the wall down through the stone, to the setting bed and into the compacted subgrade. Think of someone applying down ward pressure on your shoulders. The wall contracts changing the top of wall elevation. The wall becomes too low. In this case, such a force would only exacerbate a problem for a wall that was constructed too low initially. The prospect for soil and mulch to cascade over the wall onto the pavement is very real.

Tipping denotes a combination of horizontal and vertical forces. In tandem and at various degrees they act out of sight behind the wall. Soil, water or a combination of both can move the wall at its top while the wall remains relatively stationery at the base. Hydrostatic pressure is often the cause when the wall does not drain properly. Think of someone pushing your shoulders from the back in a forward direction while your feet are stationery.

Rotating occurs when a differential force acts horizontally and in a perpendicular direction across the length of the wall. Think of someone twisting your shoulders. This too is due to a hidden dynamic of soil, water or a combination of both behind the wall. Beyond these noteworthy considerations, this wall, however, is incomplete because the walls are ended parallel to the sidewalk.

Solution: The retaining wall needs to be rebuilt. First, the presence of an adequate setting bed needs to be confirmed. The final selection of stone requires the larger and heavier ones to be used at the base and in the middle courses of the wall with the smaller pieces at the top. The finished height of the wall needs to be much higher. A higher top of wall will prevent the loss of soil and mulch over the wall. And, the ends of the wall need to be turned away from the sidewalk and into the existing grade. Such a finish will eliminate the prospects for scouring of water and loss of soil at the wall’s inside edge. A site-specific written specification with an appropriate graphic detail would be indispensable. This holds true for all walls. There are no meaningful short cuts whether it is in design development or construction management. Completing the wall in question would make for a more attractive and structurally sound retaining wall.

|

|

Assault and Battery

Description: This silver maple has been given a hard prune. The tree has been topped.

Problem: The responsible party for this work failed to acknowledge the natural form and function of the subject tree. Known as a “soft maple” the tree has become more; not less, susceptible to storm damage. The tree’s recovery creates knobs of biomass on the lateral branches which adds mass in the wrong places. Furthermore, topping any tree makes it more vulnerable to disease and insect injury. The notion that topping reduces maintenance cost in the long run is counter-intuitive. Ultimately, it dies of a thousand misplaced cuts. This tree or any tree for that matter given a hard prune is compromised on several fronts: health, vigor and aesthetics.

Solution: This tree is on track for decline and ultimate removal. However, there is an opportunity to learn from past mistakes. Exercise due diligence in selecting an arborist or tree service. Inquire about their prevailing attitudes and values regarding preserving and protecting an existing tree. Make sure and retain only those service providers that are committed to maintaining the natural form and function of a tree. Each species of tree has its own natural form and function in any given plant community. Maintaining a tree by pruning is as much about art as science.

|

|

Help! Help!

Description: Rhododendrons have been planted in trap gravel.

Problem: Trap gravel and rhododendrons when placed together function at cross purposes. The mottled, blue-black, gravel stores and releases moisture and heat at inopportune times. In this winter scenario, the rhododendrons are losing moisture through their leaves. Any attempt to replenish the water loss through uptake of water from the roots is in competition with the gravel. Essentially, the gravel is an unwanted agent in drying out the soil. Consequently, in this competition the gravel wins and the rhododendrons lose. They were ultimately removed.

Solution: The antecedent to “right plant, right place” is a line of inquiry. Whatever the plant in question, the first question should be where does the plant occur in nature? In the case of the rhododendrons they are present in the shrub layer of an open forest. They require well drained, acid soils. The acid originates from the organic layer in the soil, i.e. forest leave litter. The plant needs protection provided in a natural setting by other shrubs, understory and canopy trees. Hence, this first question coupled with careful observations answers the following critical questions: What type of soil does the plant need? What are the water requirements? And last, how much sun or shade will the plant need or tolerate?

|

|

Open and Incomplete

Description: Yews have been planted in an open, incomplete planting bed.

Problem: A field ecologist would describe this plant community as indicative of an arid climate with less than 10 inches of annual precipitation. Due to the scarcity of rain and the presence of droughty soils, for example, plants in Arizona and New Mexico spread out and discourage diversity in both number and in species. We do not live in an arid climate, but rather in a temperate climate with an annual precipitation approaching 40 inches. Consequently, we have the benefit of filling all the niches at the groundcover, shrub, understory and canopy layer. What is presented is a cultural visual reference to the fast-food restaurant aesthetic. Who wants that? Also, one needs to be mindful of all design biases even evident in the details. Consider the plastic edge as an example. While biomorphic, serpentine edges have a place in the landscape, in this case there is way too much visual energy. One is left to wonder why.

Solution: Remove the plastic edging. Remove the trap gravel. Remove the yews. Consider the opportunities to reconfigure the size and surface area of the planting bed in a more visually pleasing way. Introduce a plant community that the available space will support. Under these conditions, a diverse mix of plants at the groundcover layer, i.e. perennials, grasses with a mass planting of evergreen shrubs as accents as well as offering winter interest would be a credible start. Perhaps a single native understory tree could be presented as a specimen plant anchoring one corner of the bed. A spaded edge would provide an informal transition between the turf and the planting bed.

|

|

Too Thin

Description: The front sidewalk is aligned between the front door and the driveway.

Problem: Homes are required to have a front sidewalk for access. Often, builders provide pavement with the shortest center line to minimize cost. The result is permitted but it is definitely not preferred. The sidewalk is aligned too close to an adjacent structure, either the house or the garage. Sometimes the full alignment encroaches on both. Consequently, the available place for plants is insufficient.

Solution: In the short-term, convert the planting bed into additional pavement. A running border of a different material, i.e. pavers or brick actually enhances the sense of arrival literally and figuratively on the margins. In the long-term, when removal and replacement of concrete is necessary, there are new opportunities. Changing the alignment of the pavement to support plants becomes possible in a restoration event. Both pavement and plants become complementary attributes maximizing the sense of arrival as an attractive landscape feature.

|

|

Too Close for Comfort

Description: Plants are located under the eave of the house.

Problem: There are three problems. First, the plants are denied adequate water to flourish in the long-run. Second, sufficient access to the structure is barred by the plants tucked-up against the building. And third, in new construction, the foundation as it continues to cure, leaches calcium into the soil, altering the pH of the soil in the direction that is too alkaline for most plants.

Solution: The foundation bed needs to be redone. A minimum 2-foot setback should be provided between the building and the finished edge of the plants. There should be clear access around the full footprint of the building for two reasons. One, the setback becomes a maintenance easement for washing or replacing a broken window, among other reasons. Two, it promotes improved air circulation around the plants. Plant beyond the eave. Better access to precipitation not only improves the health and vigor of the plants, but improves the soil as well.

|

|

Right Plant Perhaps; Wrong Location Definitely

Description: Plastic sheets and 2x4s constructed as a lean-to protect a newly planted tree during a cold snap.

Problem: The tree has been planted in the wrong place, plus it is too large as a new planting. The culture is enamored by immediate gratification. Just because one has the capacity to do something does not mean it should be done. Field experience shows that two trees; one small and one large, of the same species perform differently over time. All things being equal, the small tree will suffer less transplant shock than the large tree. Consequently, the small tree will establish itself quicker than the large tree. The small tree turns its energy and resources from survival to growth much sooner than the large one. So, five, ten, fifteen years out more times than not the small tree has matched if not exceeded in new growth the height and spread of the large tree.

Solution: Whatever the plant in question, the first question should be where does the plant occur in nature? Hence, this first question coupled with careful observations answers the following critical questions: What type of soil does the plant need? What are the water requirements? And last, how much sun or shade will the plant need or tolerate? The most salient point to be made in response to this mistake is one of patience and prudence. Buy small plants. Capture their juvenile vitality. They will tolerate transplant shock much better. If they languish or even die they can be replaced at far less cost than larger plants. Think young small plants are flexible and adaptable. Old large plants are inflexible and less adaptable.

|

|

The Benefits of Looking...

The benefits of looking, listening, feeling, smelling and tasting are the bounties present in the landscape. They are layered in experience and memory. When we deliberately change our habits and become mindful of purpose and use, we distinguish ourselves as inhabitants; rather than, occupiers of the landscape. We enhance instead of degrade the prospects for future generations to grow and flourish as well.

Visually and viscerally we are nourished and entertained. Plants are no longer just decorative embellishments, but valued members of diverse plant communities. Over any given year they go through the four seasons and present flower, fruit, seed or nut. Other compelling features include color, fragrance and texture. Furthermore, the dramatic interaction between and among fish, amphibians, reptiles, insects, birds, and mammals is a sight to behold. The forces of competition and cooperation through time aspire to a natural balance, never quite achieved.

With the broadest dispatch in any corrective action, individuals, families and neighborhoods are acknowledged and affirmed in this visual guide.

|

|

Pay Attention, Be Useful, Do No Harm

The intention of the preceding has been to draw a bright and broad distinction between trying to control as compared to guide the landscape for a specific purpose or use. The examples given lay bare the difference between the glare of clever versus the glow of smart. The former pitches solutions with a popular buzz. Performance is short term because it points to a passing fad. At its root, clever remedies are marginal, unreal, questionable and superficial. The latter teaches through explanation. Performance is long term because it is predicated on best practices. At its root smart remedies are essential, real, plausible and substantial. Hence, smart trumps clever.

Take pause; take a second, even a third look into the landscape. Consider the following positive proposition in advance of any future actions:

Offer: Cultivate an eye, a penchant for gathering information, acquiring knowledge and exercising wisdom.

Acceptance: When information, knowledge and wisdom converge, you will accept and provide care for the landscape. Visual good judgment and practical, prudent action will ensue. Memorialize in the landscape, values - natural and cultural - which promote health and vigor for all inhabitants.

|